One wine expert might say it smells of roses, another might say it smells of lychee. Two descriptions that may sound different, but will have spotted the same molecule. This is phenylethyl alcohol, which is found, for example, in Gewürztraminer.

We can smell the same thing, but we express it differently; this is also the case with lemongrass and ginger: both contain geraniol. The molecule, which we can all recognise in blackberries, for example, is similar to the lily molecule, although blackberries are a fruit, and lilies – a flower.

A wine that carries an olfactory note of freshly cut grass contains the hexanol molecule…

So many examples to awaken the curiosity of the world of Wines mixed with the world of Perfumes!

Let’s shed some light on this fascinating subject with Richard Pfister, an inspiring personality who is both an oenologist (trained at the Changins School of Oenology and Viticulture in Switzerland) and a perfumer. This expert offers his uncommon skills to the four corners of the world in sensory analysis and aromatic expression of wines.

Born into a winegrowing family on the Swiss shores of Lake Leman, Richard Pfister studied oenology at the Changins School of Engineering. Since 2002, he has been particularly interested in tasting and sensory analysis.

It was therefore natural that he did his engineering thesis on the possible relationship between oenology and perfumery. Since then, this theme has become the common thread of his professional activities, as he has worked for seven years in perfumery creation. Today, he trains and advises wine cellars all over the world (France, Spain, Switzerland, Georgia, Chile, Kazakhstan, Moldavia, Slovenia) in sensory analysis and the role of aromatic molecules: oeno-perfumery.

Vlada: You are coming from an oenological engineering background, and then you worked in perfumery. How did you become passionate about perfumery? What was that decisive moment that made you turn towards perfumery to later become a Nose at the service of wines?

Richard Pfister: I am a son of a winemaker and my father was always very interested in tasting, so he was the first trigger. Then, when I finished my studies as an oenologist, I had to prepare my engineering thesis. I was lucky to have as a subject – the methodologies of perfumers and how to apply them in the field of wine, both in terms of training and in terms of describing wines. And to master the subject, I approached different perfumers, one in particular, who became my friend. I really enjoyed talking to them, so that after my studies and after working in the wine industry as an oenologist abroad, I had the opportunity to come back to the world of perfumery, to learn and then to create for several years. So the trigger was particularly my diploma work on the methodologies of perfumers applied in the field of wine.

Vlada: Wine and Perfume: today, you perfectly combine these two fascinating fields. How do these two worlds interlink and how will they remain forever singular?

Richard Pfister: Yes, these two worlds are very much intertwined, as they are very much focused on olfaction. However, perfumery is even more so than wine, as it is almost the only sense that is emphasized. In wine, however, there is also the sense of taste, the sense of touch and the visual sense. Perfumery also likes to keep a certain aura of secrecy, which works well for it, given the image that people have of it from the outside. It also likes to remain a bit on its own, without mixing too much with the others. In that sense, these two worlds will certainly remain separate. Moreover, in perfume – we work mainly in the laboratory, mostly with synthetic molecules. We create fragrances from scratch, whereas with wine, we work with what nature gives us. This is a notable difference.

Vlada: What do you appreciate most in wine? The taste or the perfume?

Richard Pfister:Very clearly, the perfume. However, wine would be nothing if it only had perfume. And then, to have pleasure in wine, all the senses must be brought to the fore, in particular the sense of smell, taste, touch/texture, and perhaps a little bit of sight as well, even if, for me, it is much less important.

Vlada: Can we also talk about a wine fragrance in three notes (Top, Heart and Base)?

Richard Pfister: It is more complicated in wine… I separate the sensations in wine more easily in terms of intensity, the most intense being the dominant ones, then come the families, the notes and the touches… There are different ways of talking about the intensity of wine, but it’s not in the long term, except for the aromatic persistence after swallowing, which is a sign of quality.

In perfume, these three notes represent duration, persistence. The head is what comes first, the heart of the perfume is mainly felt on us, and then the base is felt after several hours, even several days, with its persistent notes.

There is this notion of duration in perfume, which is much more important than in wine. So, we can’t quite compare, even if it is interesting to take more time to taste a wine.

Vlada: Do you have « scented » dreams?

Richard Pfister: Yes, I do. The more you get interested and trained in smells, the more you can have this type of dream. It’s very surprising the first few times it happens to us because you really feel like you’re smelling the smell while you’re dreaming. And when you wake up, you’re surprised to see that there’s no reason for you to smell that smell… and that it’s just your brain that allows you to smell when you’re asleep.

Vlada: You are able to recognize the differences between hundreds of types of scents and search for individual molecules. Does developing an olfactory hypersensitivity also complicate your daily life?

Richard Pfister: Let’s say I don’t develop an olfactory hypersensitivity… I train a lot to broaden my olfactory recognition spectrum. I can also lower my sensitivity a little by being awake and paying attention to it all the time. But I don’t think I can change my sensitivity so much that I become hypersensitive. So, no, I would not say that it complicates my daily life. On the contrary, I am open to all kinds of smells and even to smells that may seem pestilential to others. An example would be the smell of excrement, such as civet, which can be used in perfumery: you can see many interesting smells in it… So I’m interested in all smells, and it makes my daily life easier. On the other hand, it’s clear that I’m very often attentive to what surrounds me in terms of smells and this may seem surprising to some.

But those who are hypersensitive and who smell scents very intensely are often handicapped by this sensitivity. They could hardly work in perfumery, for example, as they are always surrounded by strong smells.

Vlada: Would you be able to guess a person’s taste in wine based on their preference for perfume? Which wines do you think a woman would like, knowing that her favorite perfume is Coco Chanel? Are there any common molecules between that perfume and a particular wine?

Richard Pfister: There can be links, yes, even if they are not direct, as there are differences in smell between perfumes and wines. So let’s take for example Coco Chanel, an oriental-spicy perfume. It has some fruity notes at the top, such as peach, which is due to lactones… lactones that can be found in some wines like pinot gris or viognier. Coco Chanel also has vanilla in its components, which can make us think of wines aged in oak barrels. The heart of Coco Chanel is quite floral, even spicy: rose, orange blossom, clove… You can find these elements in wines, notably the clove brought by the oak barrel, for example; or on certain aromatic notes – the rose in the gewürztraminer. With Coco Chanel, I would rather establish a link with white wines; with reds, it would be a little more complicated.

Vlada: The characteristics of a wine come first and foremost from its grape variety and its terroir; other elements must also be taken into account: start of harvest, choice of yeast, fermentation temperature, maturation method, filtration… are there other factors that influence the taste and smell of wine? How can we refine the aromatic profiles already existing in a wine?

Richard Pfister: You have already mentioned a few of them, absolutely. However, there are other factors that can influence the taste and smell, such as the time spent in oak barrels, the stirring of the lees, etc. The viticultural aspects also have a lot of impact – and that interests me a lot. Depending on how the foliage is managed, whether the leaves are thinned out or not… also the way in which the vine is fed, the way in which it is given water at certain times… all this can have an impact on the aromas and taste of the wine. So yes, we can refine the aromatic profiles thanks to this, by thinking ahead.

Refining the aromatic profile that already exists in a wine – yes, we can also do that. By working on the defects in particular. We can reduce or eliminate some of them by aeration or by adding different materials such as earth or natural glues which will settle at the bottom of the tank and which we will then eliminate and which will not be found in the bottle.

Vlada: The identity of the wine is defined by its grape variety (ies), its terroir, its winemaker…

How can wine perfumery help winemakers?

Richard Pfister: I work a lot on molecules. It is really my specialty; I try to determine them by tasting and by my training. Thanks to this, we can understand much better how to act on the odors of wines. By knowing the molecules, we can look at the scientific literature to see how we can naturally influence these scents to improve the quality of the wines, their balance and their complexity. So yes, it is very useful for winemakers and oenologists to work with my method to better understand how their wine works.

Vlada: At what point/stage in the wine making process can oenoparfumery contribute to the creation of the wine’s identity? Is it an addition of molecular chemical compositions to an already produced wine or is it a work with the grapes beforehand?

Richard Pfister: It is not indeed an addition of molecules to a wine. I totally avoid this for reasons of professional ethics. It is more about working with the grapes upstream, as well as with the winemaking process.

In particular, thinking how to better reflect on the natural means that can influence the different molecules that make up the smell of a wine (which can have up to a thousand different olfactory molecules!) and how to improve the situation thanks to the greater precision acquired through perfumery.

Vlada: You apply the methodologies of perfumers in the sensory analysis of wines. If you went even further with an analysis, could you obtain from a wine of Provence an aromatic expression of a St Emilion? Wouldn’t it risk losing its identity to the wine from which it was inspired? Or even to denature the wine from which it is inspired?

Richard Pfister: My job is to highlight the characteristics of the wine itself, not to distort it. If I were asked, it would not be impossible to obtain other aromatic profiles than those naturally produced by nature. But that’s not what I’m really interested in. So yes, I will try to reinforce the natural smell of each grape variety, of each type of wine, increasing its complexity and revealing more of the aromatic potential of what it has today, if necessary.

Vlada: How is it possible to influence the aromas of a wine, without changing the perception of its terroir of origin? What are the technical, ethical and legal limits?

Richard Pfister: The aim is to reveal as much as possible of the wine as it is produced in a particular place and by a particular winemaker or oenologist. It is important to understand the notion of terroir in relation to this, because terroir is not only the soil which will have a certain influence on the smells, but also the climate, the grape variety and the human being himself. It’s very difficult to separate all these elements, each one plays a part in the creation of a wine. Afterwards, it is certain that we can try to modify the aromatic profile of a typical wine a little and get away from its typicality.

Although I don’t like the term « typicity » very much, especially since it can have a legal limit in the sense that there are tastings to determine whether a wine corresponds to a given appellation or not. So it depends a lot on the few tasters who judge it. If it falls outside the criteria, it does not have the right to the appellation. So yes, there may be limits to this, but the notion of typicity is becoming more and more open.

Vlada: Could you attribute a distinct perfume to Provence, to Burgundy… ?

Richard Pfister: Yes, even if it is not always obvious. However, let us take for example the reds that are generally made in Provence and those of Burgundy. In Provence, they are often blends – Grenache, Mourvèdre, Syrah, in particular. In Burgundy, it’s single grape varieties – Gamay or Pinot Noir – in a slightly cooler climate. The climate will inevitably influence the type of aromas that we will obtain. In Provence, we will have berries, but more ripe, like strawberry, for example. Whereas for the Burgundian Pinot Noirs, we’ll have more crunchy berries, like redcurrant and cherry. Both wines can have spicy aspects, especially the Syrah associated with Grenache and Mourvèdre: a bit more spicy complexity than just pepper, which will be more obvious in Burgundy. In Provence, you could also have additional spicy notes of aromatic plants, like rosemary, thyme, etc. So yes, we have different profiles, even if there are smells that can be similar.

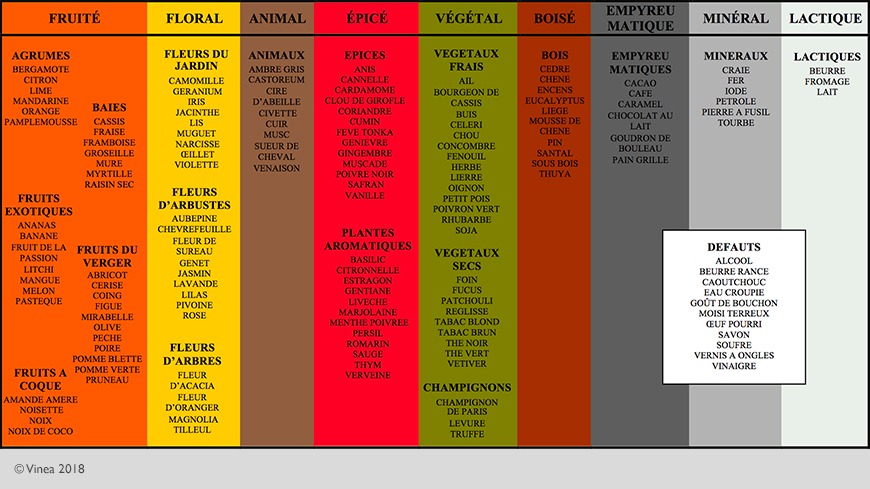

Vlada: You have developed the Œnoflair method, a tool for olfactory analysis that opens up our vocabulary during tastings. It is also a classification of the scents found in wine. In your book, you talk about 10 dominant scents: spicy, floral, animal, woody, milky, empyreumatic (e.g. toasted, roasted, smoky, aftertaste), fruity, vegetable, mineral and defective. You describe hundreds of specific odors and molecules based on the very precise analysis of numerous tasting notes. However, according to Professor Patrick Mc LEOD (Director of the Sensory Neurobiology Laboratory at the Ecole Pratique des Hautes Etudes), only 17% of odor perception in the brain depends on the product and the rest on the individual.

If we all have unique sensory equipment and experiences, how is it possible to create a common sensory response?

Richard Pfister: Very good question. I worked with Professor Patrick McLeod, by the way, who taught me a lot. I almost did a PhD thesis with him, so I am very interested in this question. The 17% that he talks about comes from a general situation, with people who are not particularly attentive to smells. The more you train, the more you will be able to reinforce the ‘product’ element over the influence of the ‘individual’ perception. In addition, the situations in which we taste, whether or not we are influenced by the outside world, whether or not we have a sensory disability, etc., all influence our impression. Nevertheless, with practice, we can reduce these influences, although we will never be able to do so completely.

One of the ways to have a common social response is to use the same training methods. Thus, by training together, we can move in the same direction. The more we train together, the more we will have the same frames of reference and the more we will reduce individual differences… but we will never manage to do it totally, that’s obvious.

Vlada: Often, when tasting wine, one goes through the impression and emotion of the taste, the memory, the memory of experiences, the comparison… it is a real « Proust’s madeleine » phenomenon.

In your work as an expert, how do you separate your own emotion from the « blind » work to describe the wine in a neutral way? Is this possible?

Richard Pfister: I practice this a lot, yes. And most of the time, when I taste a wine, whether it is professionally or for pleasure, I always have two phases: the first one is analytical and the second one is where I let my emotions out. In the first phase, I will analyse the wine, which is what interests me most. However, without the emotion that comes afterwards, it is certain that I would have much less pleasure in doing my work.

When I do work centered on sensory analysis, the analysis phase is much more important than the emotional phase that comes afterwards, but there is always a moment when I analyse in a more hedonic way, by letting my pleasure come out… How do I get really analytical in the first place: I try to cut myself off from everything around me and really concentrate on the wine, to sequence the analysis in the first phase, then I get into the precision. Then I analyse the different elements to be able to recompose them and see if they form a coherent harmony. And only then do I let the emotion come out. Therefore, yes, most of the time I try to keep the two separate, but there is always a moment when I let the emotion come out after the analysis.

To provide the best experiences, we use technologies like cookies to store and/or access device information. Consenting to these technologies allows us to process data such as browsing behavior or unique IDs on this site. Not consenting or withdrawing consent may negatively affect certain features and functions.